Are all waterholes equal from a lion's view? Exploring the role of prey abundance and catchability in waterhole visitation patterns in a savannah ecosystem

Are all waterholes equal from a lion's view? Exploring the role of prey abundance and catchability in waterhole visitation patterns in a savannah ecosystem

Dejeante, R.; Loveridge, A. J.; Macdonald, D. W.; Madhlamoto, D.; Chamaille-Jammes, S.; Valeix, M.

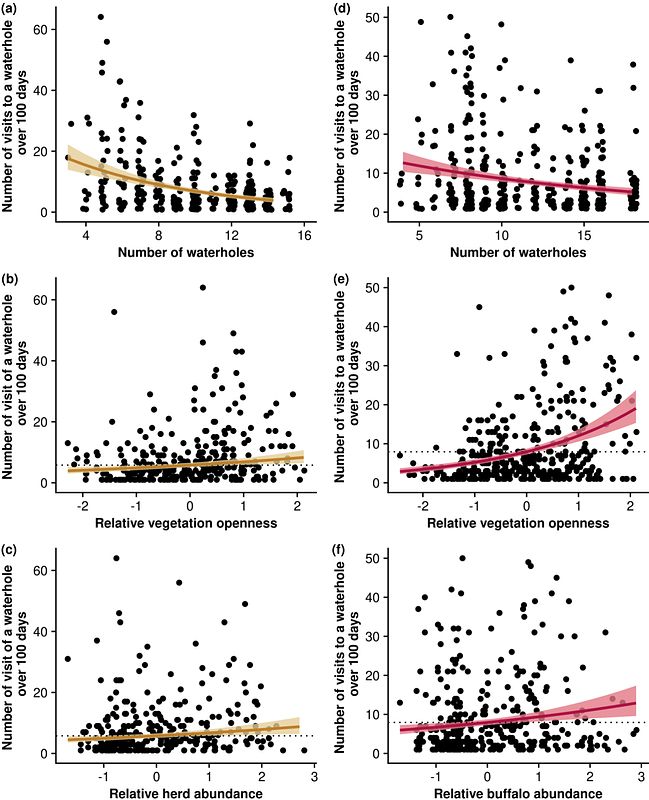

AbstractPrey abundance and catchability shape the spatial ecology of predators. Predators can select habitats where prey are more abundant to maximize encounter rate with prey, or alternatively, habitats where prey are more catchable to maximize prey capture. These hypotheses are commonly referred to as prey-abundance and prey-catchability hypotheses. Although these hypotheses are often tested at the landscape scale, little is known about how between-patch variations in prey abundance and catchability determine the space use of predators. In particular, in savannah ecosystems, waterholes are hotspots of prey and their selection by predators is classically interpreted as supporting the prey-abundance hypothesis. Here, we investigated whether between-waterhole variations in prey abundance and catchability influence the frequency and duration of lion visits to waterholes, testing the prey-abundance and prey-catchability hypotheses at the resource-patch scale. We combined datasets (1) on lion movements recorded from GPS collars deployed on 20 adult males and 16 adult females between 2002 and 2015, (2) on prey abundance evaluated from long-term, regular monitoring of waterholes conducted by the Wildlife Environment Zimbabwe and (3) on prey catchability evaluated from remote-sensing satellite imagery of vegetation cover around waterholes in Hwange National Park (Zimbabwe). Although lions did not use equally all waterholes in their territory, surprisingly, between-waterholes variations in prey abundance and catchability only slightly explained the variations in frequency -- and even less in duration -- of lion visits to waterholes. We discuss the ecological mechanisms and the limits of our work that may explain these findings. First, lions and their prey are involved in a \'shell-game\' that lead them to adopt unpredictable movement strategies. Second, lions have only access to a limited number of waterholes to spread out their hunting effort. Lastly, lions visit waterholes not only to hunt but also to interact with social mates and competitors. This work challenges the implicit assumption that all waterholes are the same from a lion\'s view and may call for further studies investigating the prey-abundance and catchability hypotheses at the resource-patch scale, especially in savannah ecosystems.